At this point, I am sure you have heard that President Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) into law in December 2017. News stations have touted this tax bill as the largest revision to the tax code since 1986. Okay, big deal. What does this mean for vacation rental management (VRM) company owners, and when do these changes take effect?

Great questions! Almost every company, including VRMs, as well as individuals, will be impacted by some aspect of the recent tax law changes. However, the real question of interest—“Will I pay more or less in taxes next year?”—involves a more complicated answer. As accountants love to say, “It depends” on the specifics of every individual’s unique circumstances. With that in mind, and without getting into specific tax situations, we will discuss the top ten tax changes attracting media attention that will likely impact the most Americans.

Almost all of these new provisions will take effect on January 1, 2018 and expire at the end of 2025. Commentary written in everyday language has been included below to describe what has changed—saving the reader from code sections, regulations, and technical jargon. Excluded are the details and nuances of the new law (there are always nuances) for brevity’s sake. The purpose of this article is to bring awareness, not to offer specific tax advice. We encourage you to speak to your tax professional to better understand these changes. To simplify the examples, only the dollar amounts for deductions, limitations, and thresholds have been given for the filing status of single and married, filing jointly, taxpayers.

10: Reduction in the Corporate (C-Corporation) Tax Rate

Although this is a major change in the corporate tax world that greatly impacts the amount of taxes these corporations pay to the United States, how these changes impact the rest of us is still just economic theory. A “C-Corporation” is a business entity structure where the actual company pays income tax on the income it earns (e.g., Coca-Cola, Walmart). The income and tax liability does not “flow through” to the individual owners of the business. The TCJA reduces the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to a flat 21 percent, including professional service corporations. This change begins January 1, 2018, and it is permanent. The intent of this reduction is to keep corporations operating in America, thus keeping jobs and cash invested in the American economy. In addition, the TCJA incentivizes companies to bring cash and other assets held overseas back to America by reducing the tax paid on these assets from 35 percent to 15.5 percent on cash and 8 percent on other assets not easily converted to cash.

9: Mortgage Interest Deduction

The new law limits the amount of deductible interest on your primary residence, or a qualifying second home, beginning in 2018. This is not a major change from the old law, which allowed taxpayers to deduct the interest paid to purchase, build, or substantially improve their primary residence, as long as the total debt on their home didn’t exceed $1,000,000, excluding home equity indebtedness. If taxpayers had a second home, then they could also deduct the mortgage interest paid to buy, construct, or improve their second home, as long as the total debt incurred for both homes didn’t exceed the $1,000,000, again excluding the home equity indebtedness threshold. The new law reduces this amount to $750,000, with the exception of grandfathered mortgages that were in place on or before December 15, 2017.

8: Home Equity Debt is No Longer Deductible

Starting in 2018, interest paid on home equity loans and lines of credit will no longer be deductible as qualified mortgage interest, unless the money borrowed was used to buy, build, or substantially improve a primary residence or second home. In addition, the total debt for these two homes cannot exceed the new mortgage limits of $750,000, or $1,000,000, including home equity indebtedness, for mortgages in place prior to Dec. 15, 2017. This means that interest paid on home equity debt used for any purpose other than to build, buy, or substantially improve a qualified home is not deductible as qualified mortgage interest. A recent release from the IRS stated that this home equity interest must be secured by the home in question. For example, if a taxpayer uses a home equity loan secured by his or her primary residence to purchase a second home, the interest paid on this home equity loan will not be deductible because it is not secured by the second home. However, if the interest on the home equity loan or line of credit was used to purchase an investment or loaned to a taxpayer’s business, this interest is not deductible as mortgage interest; rather, it is deductible as “investment” or “business” interest if it can be traced directly back to the home equity loan. To claim this interest deduction for investment or business purposes, be prepared to provide support and keep good records. Taxing agencies may challenge this claim and require documentation. Additionally, home equity debt can no longer increase the total qualified mortgage debt by $100,000 (e.g., $850,000 or $1,100,000). Prior to the change, a taxpayer could deduct qualified mortgage interest on a first and second home on debt up to $1,100,000, including home equity debt.

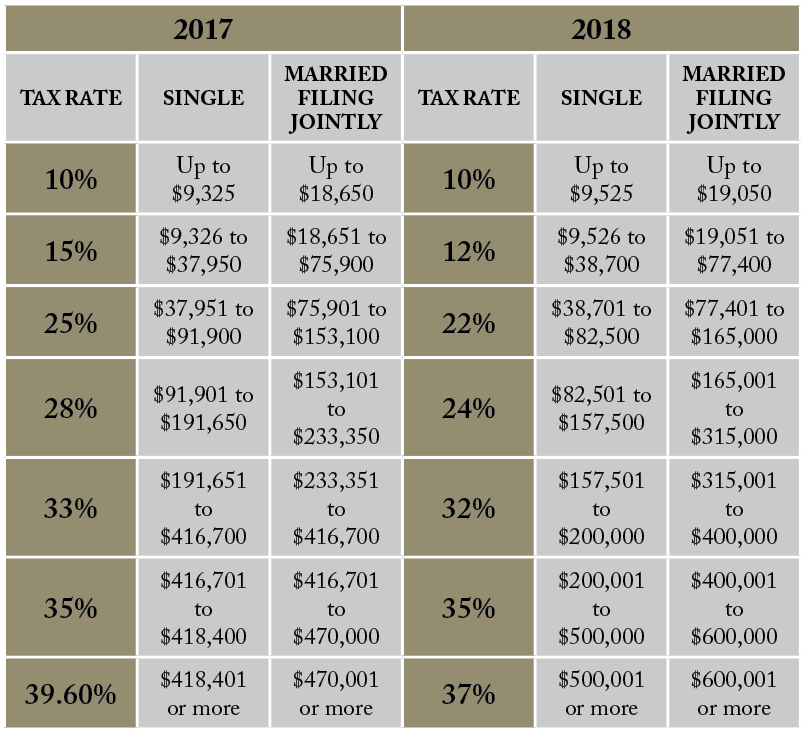

7: Expanded Tax Brackets and Lower Marginal Tax Rates

Generally, the tax brackets are modified each year by a factor adjusted for inflation; this amount is usually between 1 and 2 percent annually. In 2018, it will be no different. The tax brackets for 2018 are showing about a 2 percent increase over the brackets listed in the 2017 tables. In addition to the dollar threshold increase for each of the seven tax brackets, the marginal tax rate for six of the seven tax brackets, with the exception of the lowest bracket (10 percent), has also been reduced (see tables below). The 2018 tax brackets have also eliminated the marriage penalty tax for all but the top two brackets (35 and 37 percent).

6: Elimination of Personal Exemptions

A couple of provisions in the recent tax change have gained nothing but negative press, and this is certainly one of them. There is no way to put a positive spin on this change, or on any other change that reduces a taxpayer’s current tax deduction, when considering them individually. Instead, we must determine the impact of all the changes netted against each other before we can obtain a better understanding of the overall impact of the new law. When we consider these major changes to the tax law, we often hear that there are winners and losers. What does this mean? Simply stated, this means that, for every change that reduces tax revenue, there must be another change that increases tax revenue. In this particular case, the personal exemption is a loser, and the lower marginal tax rates are a winner. So maybe the question should be, “Am I better off as a whole under the new law?” Your response to this question may depend upon your perspective. What do I mean? Well, the answer could be based on your time frame. In 2018, while you don’t like losing your personal exemptions, your overall tax bill is lower; and your tax burden, the percentage of income required to be paid toward income tax, has also been reduced, so you are probably pretty happy. However, if these changes do not spur economic growth in America, and we continue to add to our ever-increasing national debt, your long-term perspective may be a little less enthusiastic. These same parameters should also be considered when looking at the impact of the limitation of state and local taxes, discussed below, which is being capped at $10,000.

5: Increase in the Child Tax Credit and New Non-Refundable Credit

One way the new tax law tries to offset the loss of personal exemptions is by increasing the current child tax credit of $1,000 to $2,000 on eligible children, and increasing the refundable portion of this credit from $1,000 to $1,400. An eligible child is one that is 16 years old or younger, is a dependent of the taxpayer, and meets the other qualifications—relationship, citizenship, support, and residence tests. In addition to the dollar increase of this tax credit, the new law has also increased the income taxpayers can earn before this tax credit is phased out for those making too much money. For example, in 2017, taxpayers filing a joint tax return would begin to lose their child tax credit once their adjusted gross income exceeded $110,000. In 2018, the income phaseout for those same taxpayers now begins at $400,000. For single taxpayers, the income threshold has been raised from $75,000 to $200,000. This means that many more Americans will now qualify for the child tax credit. In addition, the TCJA has also enacted a new $500 non-refundable tax credit for other dependents who do not qualify for the child tax credit (e.g., a qualifying child 17 or older, or a qualifying relative).

4: Expanded Depreciation Deductions

In recent years, the tax code has been generous in allowing businesses to immediately deduct the costs of placing new business assets into service to reduce taxable income, versus taking these deductions over several years (class life of the asset). This provision encouraged firms to reinvest cash back into their business for new equipment in the  hope that it would lead to economic growth. The updated provisions in the TCJA increase these limits even more. The Section 179 limit, previously $510,000, has now been increased to $1 million on purchases of eligible property, up to $2.5 million in 2018. (The old limit was $2 million.) In addition, Section 179 can now be applied to tangible personal property used in connection with furnishing lodgings, aka rental properties, starting in 2018. Changes to bonus depreciation allow taxpayers to immediately expense 100 percent of the purchase price on eligible property and equipment, compared with only 50 percent in 2017. Now bonus depreciation also includes qualified “used” property for the first time.

hope that it would lead to economic growth. The updated provisions in the TCJA increase these limits even more. The Section 179 limit, previously $510,000, has now been increased to $1 million on purchases of eligible property, up to $2.5 million in 2018. (The old limit was $2 million.) In addition, Section 179 can now be applied to tangible personal property used in connection with furnishing lodgings, aka rental properties, starting in 2018. Changes to bonus depreciation allow taxpayers to immediately expense 100 percent of the purchase price on eligible property and equipment, compared with only 50 percent in 2017. Now bonus depreciation also includes qualified “used” property for the first time.

3: Increase in the Standard Deduction Amount

This is one provision in the new tax law that will simplify taxes for many Americans. According to the most recent information pulled from the IRS (2013 tax returns), approximately 30 percent of American households currently itemize deductions on their individual tax returns. With the standard deduction amounts almost doubled, early estimates predict that this number could drop to as low as 10 percent. The standard deduction amount for single taxpayers in 2018 is $12,000, compared with $6,300 in 2017; it is $24,000 for married taxpayers filing a joint return, versus $12,700 in 2017.

2: Limitation on State and Local Taxes to $10,000

No change in the recent tax law has caused as much controversy, or warranted more air time, than the $10,000 limitation on state and local taxes. This one change has several states suing over the constitutionality of the new law as they try to figure workarounds for their residents and workers affected by this limitation. As I stated earlier, there is no way to be in favor of this kind of change, or any change that reduces individual current deductions, especially when considering the effects of the new law’s total package. Have you run your numbers? Will you pay more or less tax in 2018 versus 2017 if everything else stays the same? If not, you may want to crunch the numbers before you push for changes. Nevertheless, don’t be surprised if this provision is tweaked over the next couple of years because of the public outcry.

1: 20 Percent Deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI)

For tax professionals and small business owners, this item has by far attracted the most attention and raised the most questions about how it will actually work and who will actually qualify for it. It is also probably the most complex provision in the new tax law. For now, I will only try to explain the very basic parameters within this new deduction. The 20 percent deduction is available to all business owners who report their business income on their individual tax returns, subject to certain income limitations. If these income thresholds are met or exceeded, the amount of the deduction could be limited or eliminated. The businesses qualifying for the deduction include sole proprietors, single-member LLCs, individual rental property owners, shareholders of S corporations, and partners in a partnership.

In general, the 20 percent QBI deduction is calculated by multiplying a business’ net income by 20 percent to determine the amount of the deduction. For example: $100,000 of net income x 20% = $20,000 deduction. When determining the QBI of the taxpayer’s business, be aware that this amount does not include the wages paid to a shareholder of an S corporation or the guaranteed payments made to a partner. After calculating the 20 percent QBI deduction, the next step is to see if the taxpayer’s income level exceeds the taxable income threshold placed on this deduction before other limitations apply.

Limitations are placed on the 20 percent deduction when a single taxpayer’s taxable income reaches $157,500 and the taxable income of a married taxpayer filing jointly reaches $315,000. Once these taxable income levels are reached, the taxpayer’s 20 percent deduction is limited to the lesser of the 20 percent QBI, or the greater of 50 percent of the wages paid by the business, or 25 percent of the wages paid by the business plus 2.5 percent of the original cost basis of depreciable property owned by the business. Simple, right? Unfortunately, we are just getting started.

If the taxpayer’s QBI derives from a specified service-related business, such as those operated by doctors, lawyers, accountants, and so on, the taxpayer’s 20 percent deduction begins to phase out once these same income levels are reached—$157,500 for single taxpayers and $315,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly. They completely disappear once the business owner’s taxable income exceeds $207,500 for a single taxpayer’s specified service business, or $415,000 for a married business owner filing a joint tax return.

Because this provision is so new, and authoritative guidance has not yet been issued, some caution should be exercised when projecting your future 20 percent QBI deduction. One area of concern applies to rental property owners who rent out their property on triple net leases. Will they qualify? And what is a triple net lease? With a triple net lease, the property owner requires the tenant to be responsible for all ongoing expenses of the rental property, such as real estate taxes, maintenance, insurance, utilities, and so on. At this point, experts are predicting that triple net lease properties will not qualify for the deduction because they are not considered an active trade or business.

Have you had enough of tax simplification yet? Don’t hold your breath waiting for your tax postcard to arrive in the mail before filing your 2018 tax returns. Although many provisions in the new tax code are far from simple, overall we believe that most taxpayers will see tax savings in 2018. Some will see large savings, whereas others will pay more. Be proactive, be prepared, and plan for your tax day.

We hope that we have you thinking and asking yourself questions about these changes. Of course, as always, we encourage you to talk to your tax professional.

What is the gross amount a qualifying relative can earn in 2018

to still be considered a dependent?